Informing U.S. engagement with the world

![Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Dan Caine speaks during a press conference with U.S. President Donald Trump at Mar-a-Lago club on January 03, 2026, in Palm Beach, Florida.]()

![An Iranian woman holding a poster depicting Iran's Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei walks under a large flag during the forty-seventh anniversary of the Islamic Revolution in Tehran, Iran on February 11, 2026. Majid Asgaripour/West Asia News Agency via Reuters]()

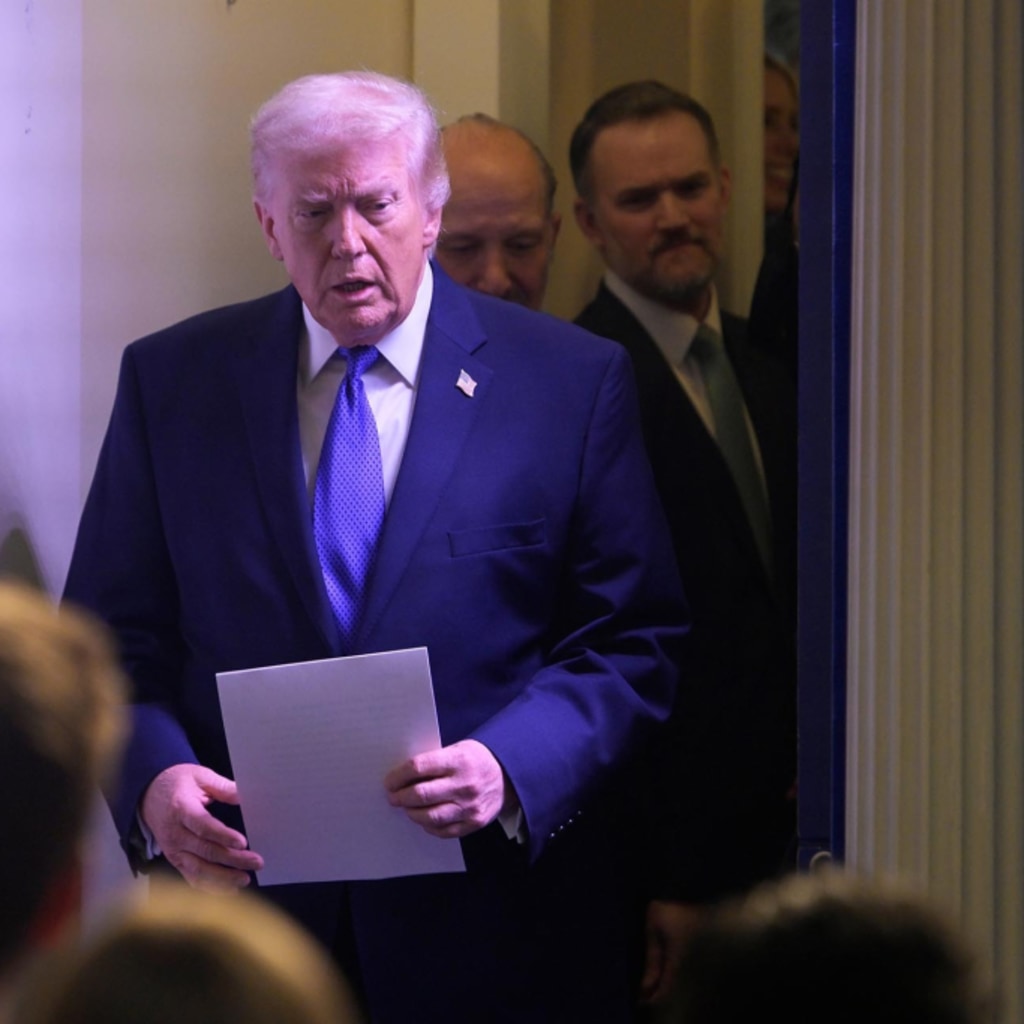

The Supreme Court Clipped Trump’s Tariff Powers—and Opened New Trade Battles

By Jennifer Hillman

![President Donald Trump speaks about the Supreme Court's tariff decision during a press briefing, on February 20, 2026 at the White House in Washington D.C.]()

![<p>Ukrainian soldier prepares a drone for flight at a training area on February 8, 2025 in Donetsk Oblast, Ukraine.</p>]()

![Image of Trump entering Congress.]()

CFR Spotlights

The War in Ukraine

Russia’s invasion has reshaped European security, strained Western alliances, and tested the limits of international resolve. But, as the conflict enters its fifth year, the terms of any eventual settlement appear to remain as contested as the front lines themselves.

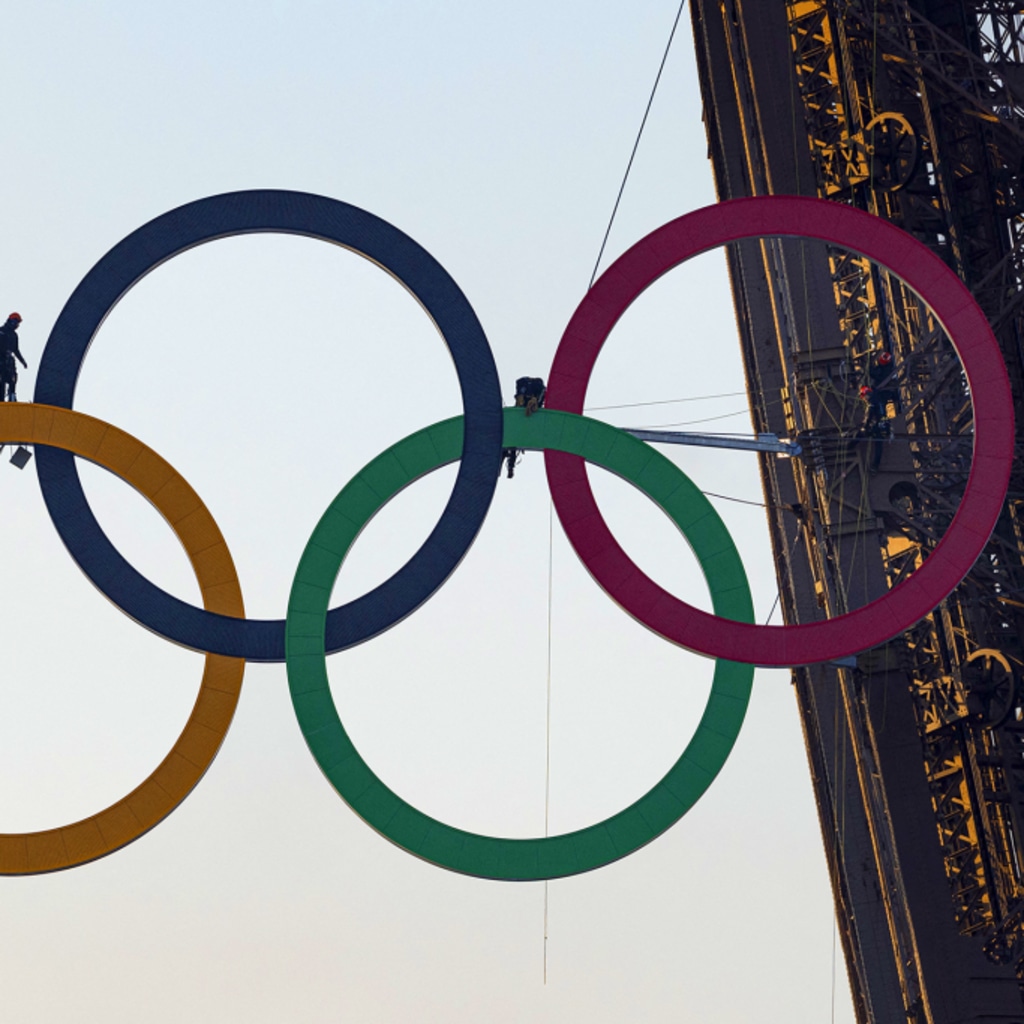

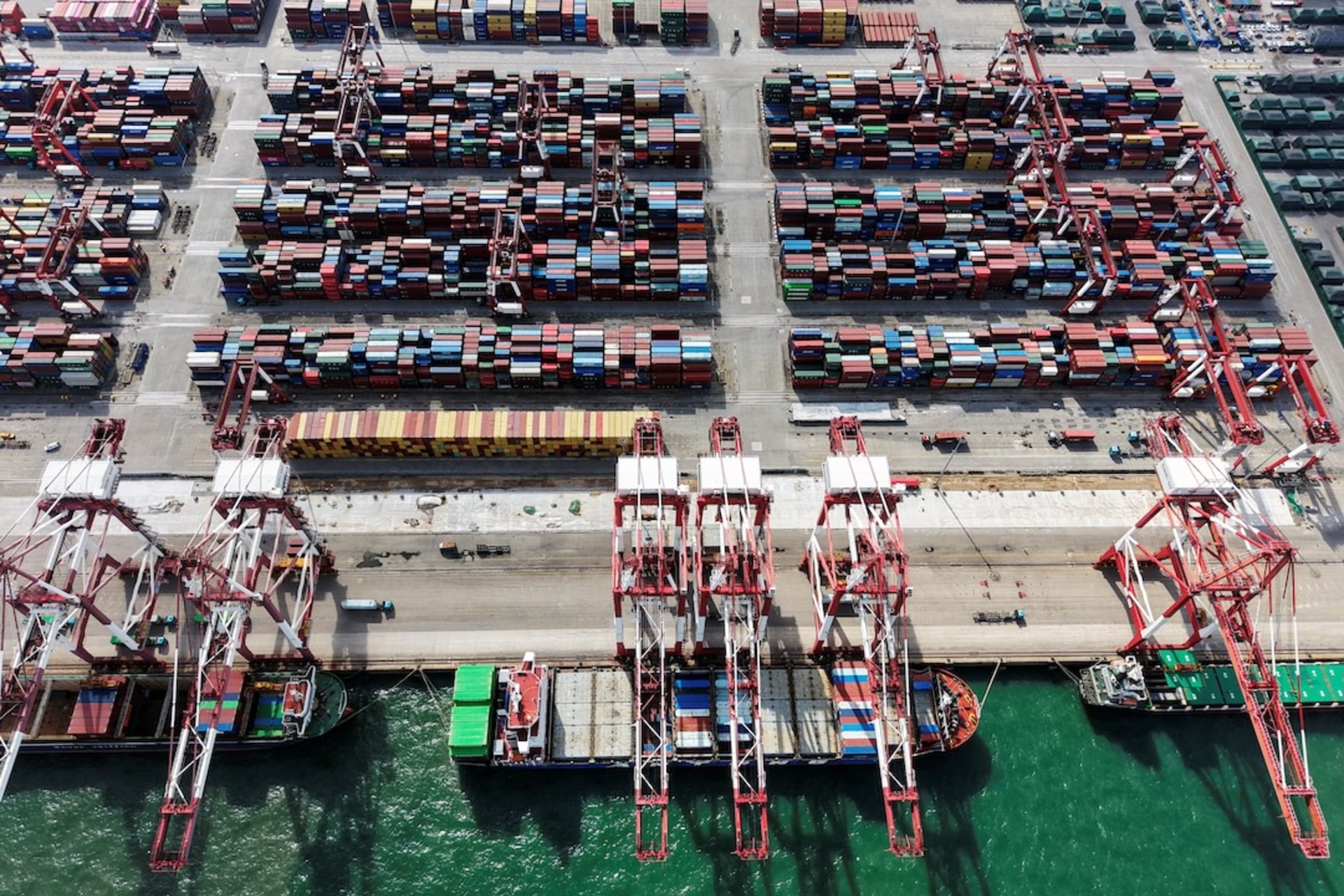

Trade and Tariffs

A landmark Supreme Court decision striking down the president’s use of emergency powers to impose tariffs has upended the legal foundation of Trump’s trade agenda — forcing a reckoning over which tariff authorities remain viable and what comes next for U.S. trade policy.

The World, Explained

Use CFR’s backgrounders and explainers to dig deeper into critical global issues.

The Spillover Podcast: Trump’s Tariffs Struck Down

The Spillover, CFR’s new weekly series, traces the ripple effects of global events across geopolitics, economics, technology, and finance. In a special episode, host Rebecca Patterson is joined by CFR President Michael Froman, a former U.S. trade representative, to unpack Friday’s Supreme Court decision that struck down Trump’s use of the International Emergency Economic Powers Act (IEEPA) to impose tariffs.

Follow on: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | YouTube

Newsletters

The Daily News Brief

CFR Events

View AllCFR in the News

View AllPublications

CFR publishes reports and papers for the interested public, the academic community, and foreign policy experts.